The Fourier Transform is often applied to signal processing and other analyses. It allows a signal to be transformed between the time domain and the frequency domain. The efficient Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm is implemented in Julia using the FFTW library.

1D Fourier Transform

Let’s start by looking at the Fourier Transform in one dimension. We’ll create test data in the time domain using a wide rectangle function.

f = [abs(x) <= 1 ? 1 : 0 for x in -5:0.1:5];

length(f)

101

This is what the data look like:

We’ll transform the data into the frequency domain using fft().

F = fft(f);

typeof(F)

Array{Complex{Float64},1}

length(F)

101

F = fftshift(F);

The frequency domain data are an array of Complex type with the same length as the time domain data. Since each Complex number consists of two parts (real and imaginary) it seems that we have somehow doubled the information content of our signal. This is not true because half of the frequency domain data are redundant. The fftshift() function conveniently rearranges the data in the frequency domain so that the negative frequencies are on the left.

This is what the resulting amplitude and power spectra look like:

The analytical Fourier Transform of the rectangle function is the sinc function, which agrees well with numerical data in the plots above.

2D Fourier Transform

Let’s make things a bit more interesting: we’ll look at the analogous two-dimensional problem. But this time we’ll go in the opposite direction, starting with a two-dimensional sinc function and taking its Fourier Transform.

Building the array of sinc data is easy using a list comprehension.

f = [(r = sqrt(x^2 + y^2); sinc(r)) for x in -6:0.125:6, y in -6:0.125:6];

typeof(f)

Array{Float64,2}

size(f)

(97,97)

It doesn’t make sense to think about a two-dimensional function in the time domain. But the Fourier Transform is quite egalitarian: it’s happy to work with a temporal signal or a spatial signal (or a signal in pretty much any other domain). Let’s suppose that our two-dimensional data are in the spatial domain. This is what it looks like:

Generating the Fourier Transform is again a simple matter of applying fft(). No change in syntax: very nice indeed!

F = fft(f);

typeof(F)

Array{Complex{Float64},2}

F = fftshift(F);

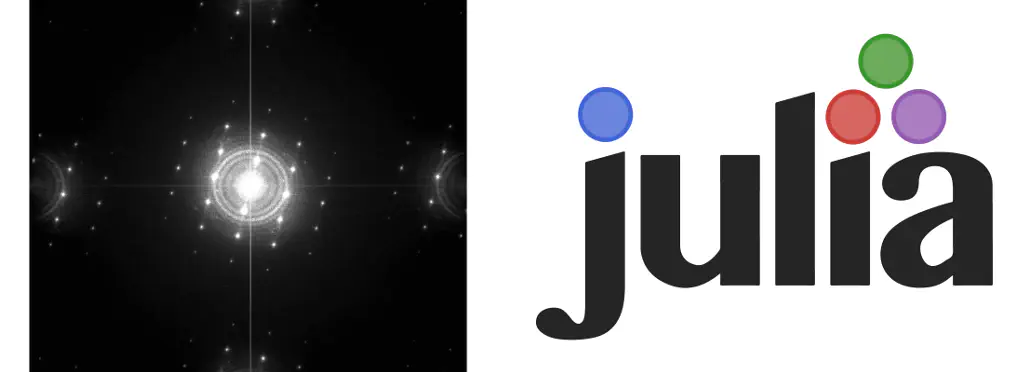

The power spectrum demonstrates that the result is the 2D analogue of the rectangle function.

Higher Dimensions and Beyond

It’s just as easy to apply the FFT to higher dimensional data, although in my experience this is rarely required.

Most of the FFTW library’s functionality has been implemented in the Julia interface. For example:

- it’s possible to generate plans for optimised FFTs using

plan_fft(); dct()yields the Discrete Cosine Transform;- you can exploit conjugate symmetry in real transforms using

rfft(); and - it’s possible to run over multiple threads using

FFTW.set_num_threads().

Watch the video below in which Steve Johnson demonstrates many of the features of FFTs in Julia.