In two previous installments we considered various aspects of the given name data from 1880 to the present day compiled by the Social Security Administration. In this final article I’ll take a look at unisex names and nicknames.

Of the 93889 names in the database, 8914 (just less than 10%) have been used for both genders. These “unisex names” (also known as epicene or gender-neutral names) are becoming progressively more common.

Some names have always been used for both boys and girls. New names are also continuously being introduced, many of which are also immediately applied to both genders. Bennie was unisex from its first appearance in 1880. Bobby has been applied to both genders from its first recorded use in 1900, although over time it has been given to girls less often. Clare also started out as a unisex name in 1880, but over time its use for boys has declined. There have been no boys named Clare for over a decade. Cyncere has only been in use since 1999 but has been applied consistently to both genders. Delorean was first used as an unisex name in 1982. It has recently been given only to boys though. Not too surprisingly, it was first used between 1981 and 1983 when the DeLorean DMC-12 was being manufactured (some years before the release of Back to the Future in 1985!). Halley was introduced as a given name in 1910, when Halley’s Comet was visible to the naked eye. Interestingly, although Halley was given to boys and girls in similar numbers in 1910, it subsequently became a girls’ name. In 1985 and 1986 (years around the re-appearance of the comet), there was a resurgence of boys named Halley.

At the other end of the spectrum, some names were traditionally used exclusively for either girls or boys, but are now being applied to both. Halsey was originally a boys’ name and was only given to a girl for the first time in 1981. Indiana was a name used only for girls until 1990, when it was adopted as a boys’ name as well. This might be linked to the Indiana Jones movies which appeared in the 1980s. It makes one wonder why George Lucas chose this historically feminine name for his overtly masculine hero? Other examples of names which only recently became unisex are Campbell, Moe, Embry and Franc.

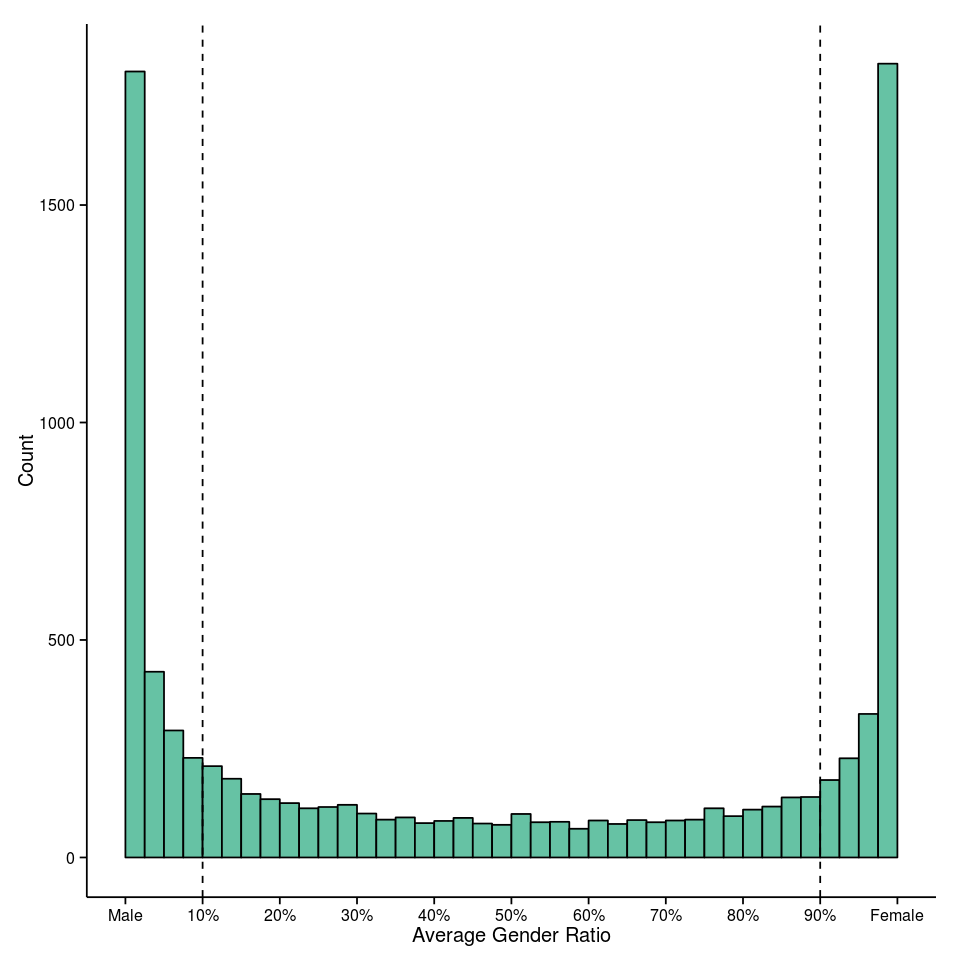

Are unisex names shared evenly between the sexes? The histogram below shows the distribution of unisex names in terms of their proportional use for each gender. The peak on the left represents names applied almost exclusively to boys, while the peak on the right is the equivalent for girls. The distribution is distinctly bathtub shaped: the vast majority of names are still applied predominantly to one gender or the other and therefore fall in the extreme bins on the left and right. The peak on the left includes names like Matt, Bart and Norbert, which have been given to only a few girls. The peak on the right captures predominantly girls’ names like Daphne, Sybil and Scarlett, which have been assigned to only a handful of boys. Clearly these are names which are broadly considered to be either masculine or feminine.

In the middle of the plot lie names which have an even split between boys and girls. Here we have, for example, Gabriyel, Keagyn, Laetyn, Nicola, Jacyn, Kobi, Babe, Tracy, Rael, Codie, Adrean, Daine, Germany, Burnice, Mikah, Shelby and Quanta. Interestingly, these truly unisex names are generally ones that have only entered popular use in recent years.

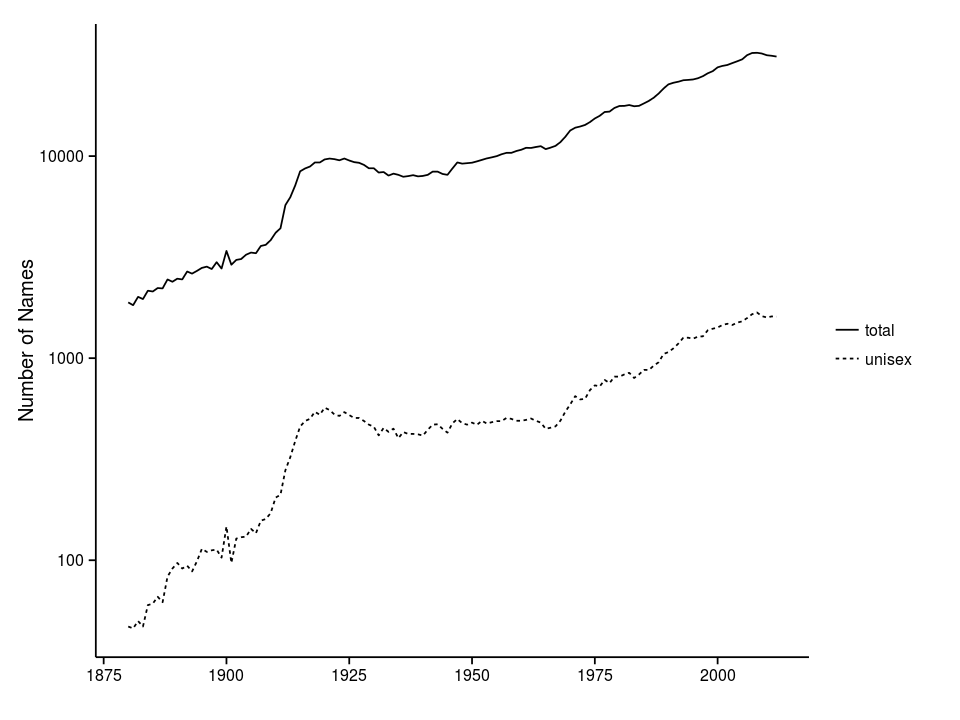

Although in some countries unisex names are not used due to legal or social restrictions, they are fairly common in the USA. But just how common are they? In order to restrict our attention to those names which are truly unisex, we’ll consider only names with a gender ratio between 10% and 90% (between the vertical dashed lines on the histogram above). To determine whether the use of these names is accelerating, we can compare the number of unisex names to the total number of names in use. The plot below shows how the number of given names climbs from 1889 in 1880 to 30579 in 2014, an escalation of more than 1600%. By contrast, the number of unisex names expands from 47 to 1598 over the same time period, which is roughly an increase of 3400%. The proportion of names which are being used for both genders has grown from 2.5% to 5.2%: clearly unisex names are becoming more fashionable.

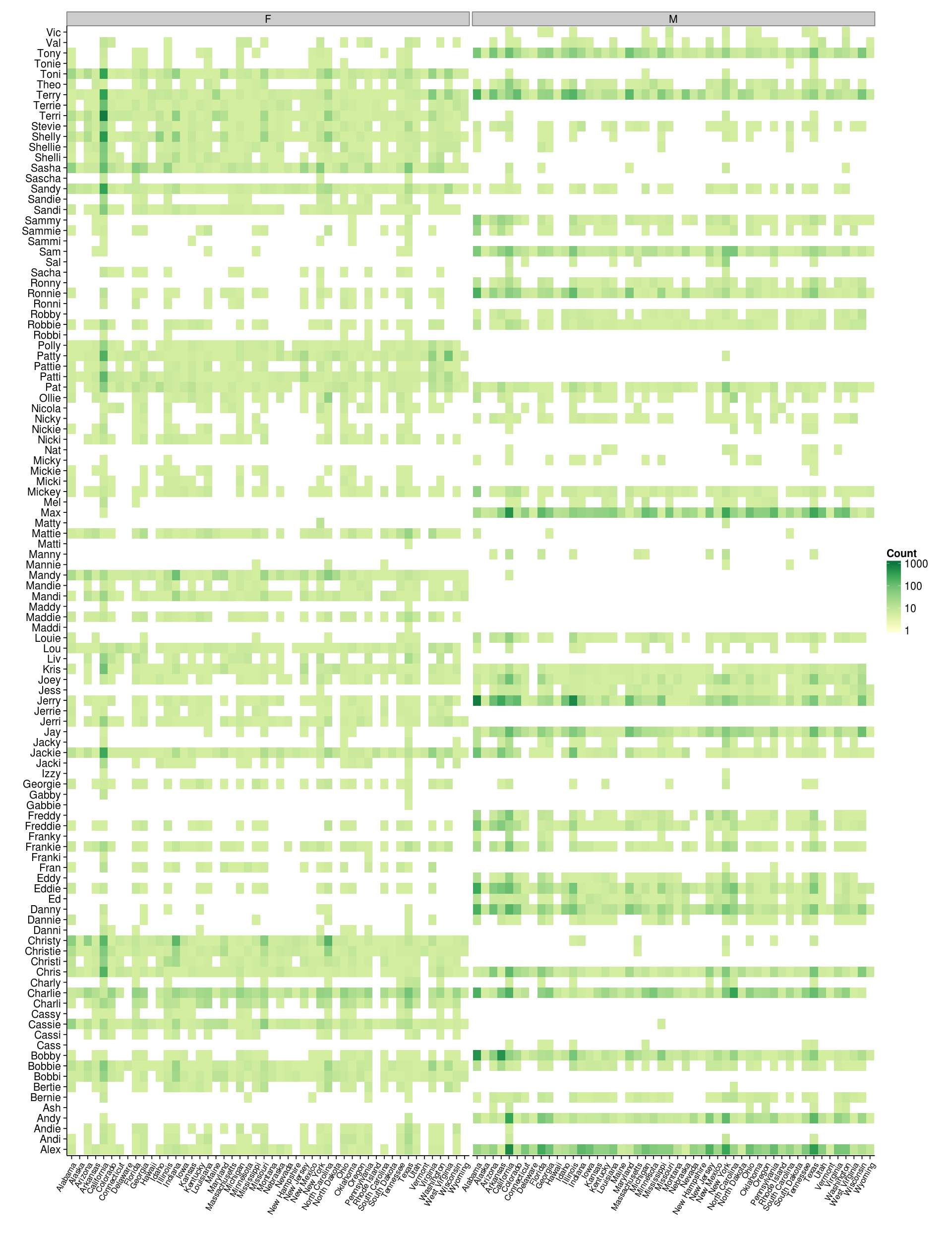

There is also a growing tendency for children to be given names which would traditionally be considered as nicknames. The plot below shows the incidence of selected nicknames as given names. Many of these nicknames are unisex as well. For example, Terry, Chris and Alex are used for both girls and boys across almost all states.

Nicknames are derived in a variety of ways. Some are contractions of longer names, like Sam from Samuel, while others are expansions of shorter names, like Frankie derived from Frank. Letter swapping is another route to nicknames, like Izzy from Isaac, Isaiah, Isabel or Isabella, and Joey from Joseph, Josephine or Joanna. Both Izzy and Joey are obviously unisex too! Still others are formed by truncating a name and adding i, ie or y, for example, Maddi, Charlie or Sammy. Many nicknames are homophones, pronounced the same but spelled differently, such as Charli, Charlie and Charly.

Which unisex names are going to be popular in the next few years? Dakota, Justice, Jessie and Casey have rated highly in recent years and are likely to be popular in the future too. Other possibilities are Riley, Quinn and Skyler. Of course, you don’t need to follow the crowd. There is a host of other names ranging from the common to the esoteric. How about Windsor, Rhen or Tyme?