This series of articles was written as support material for Statistics exercises in a course that I’m teaching for iXperience. In the series I’ll be using illustrative examples for wagering on a variety of Sportsbook events including Horse Racing, Rugby and Tennis. The same principles can be applied across essentially all betting markets.

Odds

To make some sense of gambling we’ll need to understand the relationship between odds and probability. Odds can be expressed as either “odds on” or “odds against”. Whereas the former is the odds in favour of an event taking place, the latter reflects the odds that an event will not happen. Odds against is the form in which gambling odds are normally expressed, so we’ll focus on that. The odds against are defined as the ratio, L/W, of losing outcomes (L) to winning outcomes (W). To link these odds to probabilities we note that the winning probability, p, is W/(L+W). The odds against are thus equivalent to (1-p)/p.

To make this more concrete, consider the odds against rolling a 6 with a single die. The number of losing outcomes is L = 5 (for all of the other numbers on the die: 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) while the number of winning outcomes is W = 1. The odds against are thus 5/1, while the winning probability is 1/(5+1) = 1/6.

Fractional Odds

Fractional odds are quoted as L/W, L:W or L-W. From a gambler’s perspective these odds reflect the net winnings relative to the stake. For example, fractional odds of 5/1 imply that the gambler stands to make a profit of 50 on a stake of 10. In addition to the profit, a winning gambler gets the stake back too. In the previous scenario, the gambler would receive a total of 60. Conversely, factional odds of 1/2 would pay out 10 for a stake of 20. Odds of 1/1 are known as “even odds” or “even money”, and will pay out the same amount as was wagered.

The numerator and denominator in fractional odds are always integers.

In a fair game a player who placed a wager at fractional odds of L/W would reasonably expect to win L/W times his wager.

Decimal Odds

Decimal odds quote the ratio of the full payout (including original stake) to the stake. Using the same symbols as above, this is equivalent to the ratio (L+W)/W or 1+L/W. The decimal odds are numerically equal to the fractional odds plus 1. In a fair game the decimal odds are also the inverse of the probability of a winning outcome. This makes sense because the inverse of the decimal odds is W/(L+W).

From a gambler’s perspective, decimal odds reflect the gross total which will be paid out relative to the stake. For example, decimal odds of 6.0 are equivalent to fractional odds of 5/1 and imply that the gambler stands to get back 60 on a stake of 10. Similarly, decimal odds of 1.5 are the same as fractional odds of 1/2, and a winning gambler would get back 30 on a wager of 20.

Decimal odds are quoted as a positive number greater than 1.

Odds and Probability

As indicated above, there is a direct relationship between odds and probabilities. For a fair game, this relationship is simple: the probabilities are the reciprocal of the decimal odds. And for a fair game, the sum of the probabilities of all possible outcomes must be 1.

The reciprocal relationship between decimals odds and probabilities implies that outcomes with the lowest odds are the most likely to be realised. This might not tie up with the conventional understanding of odds, but is a consequence of the fact that we are looking at the odds against that outcome.

Example: Fair Odds on Rugby

The Crusaders are playing the Hurricanes at the AMI Stadium. A bookmaker is offering 1/2 odds on the Crusaders and 2/1 odds on the Hurricanes. These fractional odds translate into decimal odds of 1.5 and 3.0 respectively. Based on these odds, the implied probabilities of either team winning are

> (odds = c(Crusaders = 1.5, Hurricanes = 3))

Crusaders Hurricanes

1.5 3.0

> (probability = 1 / odds)

Crusaders Hurricanes

0.66667 0.33333

The Crusaders are perceived as being twice as likely to win. Since they are clearly the favourites for this match it stands to reason that there would be more wagers placed on the Crusaders than on the Hurricanes. In fact, on the basis of the odds we would expect there to be roughly twice as much money placed on the Crusaders.

A successful wager of 10 on the Crusaders would yield a net win of 5, while the same wager on the Hurricanes would stand to yield a net win of 20. If we include the initial stake then we get the corresponding gross payouts of 15 and 30.

> (odds - 1) * 10 # Net win

Crusaders Hurricanes

5 20

> odds * 10 # Gross Win

Crusaders Hurricanes

15 30

In keeping with the reasoning above, suppose that a total of 2000 was wagered on the Crusaders and 1000 was wagered on the Hurricanes. In the event of a win by the Crusaders the bookmaker would keep the 1000 wagered on the Hurricanes, but pay out 1000 on the Crusaders wagers, leaving no net profit. Similarly, if the Hurricanes won then the bookmaker would pocket the 2000 wagered on the Crusaders but pay out 2000 on the Hurricanes wagers, again leaving no net profit. The bookmaker’s expected profit based on either outcome is zero. This does not represent a very lucrative scenario for a bookmaker. But, after all, this is a fair game.

From a punter’s perspective, a wager on the Crusaders is more likely to be successful, but is not particularly rewarding. By contrast, the likelihood of a wager on the Hurricanes paying out is lower, but the potential reward is appreciably higher. The choice of a side to bet on would then be dictated by the punter’s appetite for risk and excitement (or perhaps simply their allegiance to one team or the other).

The expected outcome, which weights the payout by its likelihood, of a wager on either the Crusaders or the Hurricanes is zero.

> (probability = c(win = 2, lose = 1) / 3) # Wager on Crusaders

win lose

0.66667 0.33333

> payout = c(win = 0.5, lose = -1)

> sum(probability * payout)

[1] 0

> (probability = c(win = 1, lose = 2) / 3) # Wager on Hurricanes

win lose

0.33333 0.66667

> payout = c(win = 2, lose = -1)

> sum(probability * payout)

[1] 0

Again this is because the odds represent a fair game.

Most games of chance are not fair, so the situation above represents a special (and not very realistic) case. Let’s look at a second example which presents the actual odds being quoted by a real bookmaker.

Example: Real Odds on Tennis

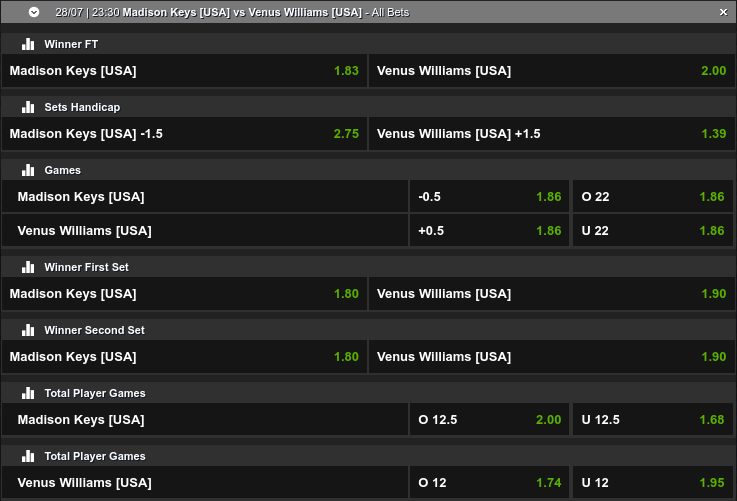

The odds below are from an online betting website for the tennis match between Madison Keys and Venus Williams. These are real, live odds and the implications for the player and the bookmaker are slightly different.

We’ll focus our attention on the overall winner, for which the decimal odds on Madison Keys are 1.83, while those on Venus Williams are 2.00.

> (odds = c(Madison = 1.83, Venus = 2.00))

Madison Venus

1.83 2.00

> (probability = 1 / odds)

Madison Venus

0.54645 0.50000

The first thing that you’ve observed is that the implied probabilities do not sum to 1. We’ll return to this point in the next article.

The odds quoted for each player very similar, which implies that the bookmaker considers these players to be evenly matched. Madison Keys has slightly lower odds, which suggests that she is a slightly stronger contender. A wager on either player will not yield major rewards because of the low odds. However, at the same time, a wager on either player has a similar probability of being successful: both around 50%.

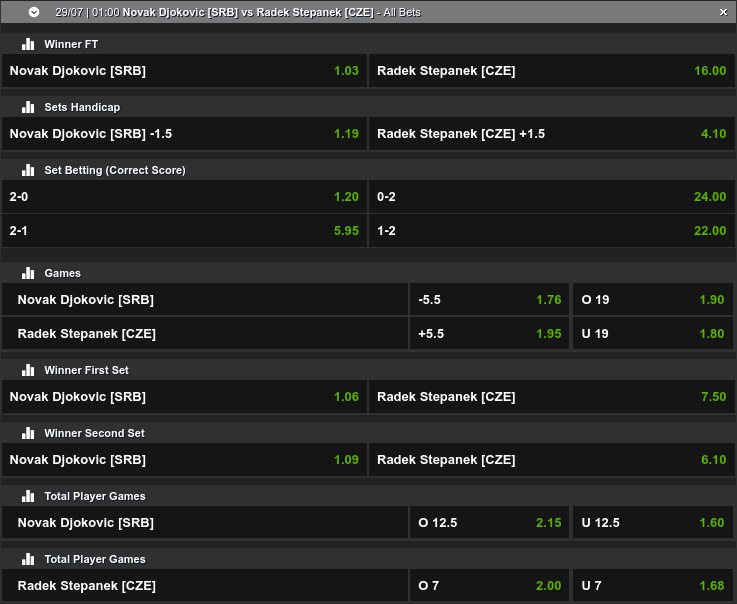

Let’s look at another match. Below are the odds from the same online betting website for the game between Novak Djokovic and Radek Stepanek.

The odds for this game are profoundly different to those for the ladies match above.

> (odds = c(Novak = 1.03, Radek = 16.00))

Novak Radek

1.03 16.00

> (probability = 1 / odds)

Novak Radek

0.97087 0.06250

Novak Djokovic is considered to be the almost certain winner. A wager on him thus has the potential to produce only 3% winnings. Radek Stepanek, on the other hand, is a rank outsider in this match. His perceived chance of winning is low. As a result, the potential returns should he win are large.

To find out more about converting between different forms of odds and the corresponding implied probabilities, have a look at this tutorial. If you want to learn more, take a look at this video which very clearly explains the concepts described in this post.

In the next instalment we’ll examine how bookmakers’ odds ensure their profit yet provide a potentially rewarding (and entertaining) experience for gamblers.