I was invited to give a talk at Digifest (Durban University of Technology) on 10 November 2017. Looking at the other speakers and talks on the programme I realised that my normal range of topics would not be suitable.

I needed to do something more in line with their mission to “celebrate the creative spirit through multimedia projects from disciplines such as visual and performing arts” and to promote “collaboration across art, science and technology”. Definitely outside my current domain, but consistent with many of the things that I have been aspiring to.

To be honest, I was pleased to be invited, but when I sat down to consider what I would talk about, I found myself at a loss. I’m not currently engaged in anything that ticks many of those boxes.

But I am loathe to turn down an opportunity to speak. I made a plan. In retrospect it was not a terribly good plan. But it was workable. I decided to speak about gauging sentiment relating to the city of Durban using data from Twitter. This post touches on some of my results.

Data Acquisition

Given that I had not much more than two weeks to gather data, I needed to get cracking. The first thing I did was write up a script using the {rtweet} package to stream tweets which matched either “Durban” or “eThekwini”. I streamed data in 5 minute segments and dumped the raw results to file. Parsing of the tweets was deferred in order to minimise latency.

With data gathering in the background I was able to focus on my analysis. I don’t do much text analytics, so I found Text Mining with R to be invaluable. Simply adapting portions of those analyses to the Twitter data immediately produced results.

I am not going to present all of them here, but I’ll show some of the (limited) highlights. With more extensive data I expect that the results would be more informative.

Tweeting Time

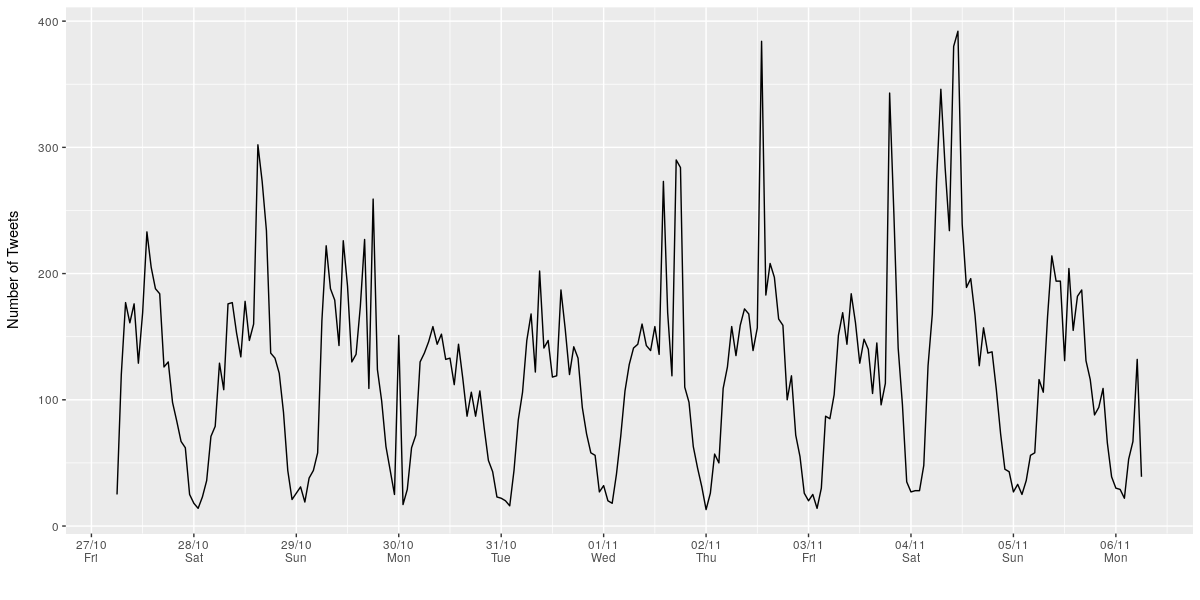

When do people express their thoughts about Durban on Twitter? The time series below shows the limited extent of my data. However, it’s clear that there’s a well formed diurnal cycle with significant variability from day to day.

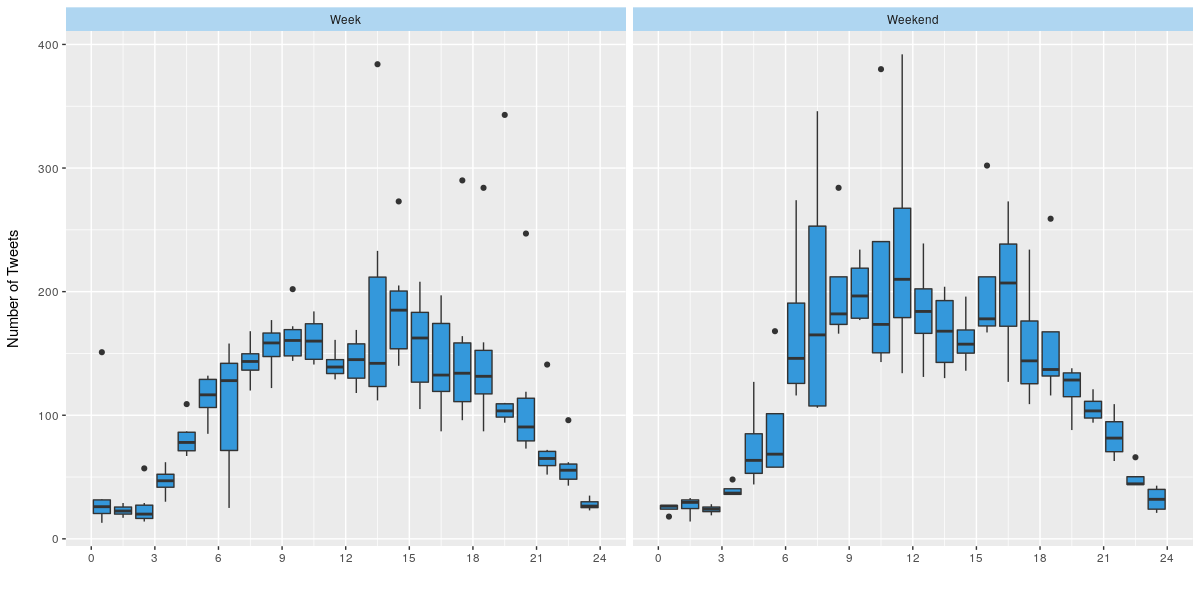

Aggregating the data by hour and splitting out week days from the weekend resulted in the plot below. In broad strokes the diurnal pattern is similar during the week and over the weekends. But there are also some very clear differences. The number of tweets per hour picks up steadily during the morning on week days, but on weekends there’s a dramatic jump at around 07:00. This might be an artifact of my limited data. Another observation (which I believe is definitely not an artifact!) is the significant jump in the number of tweets at lunch time on week days.

Zipf’s Law

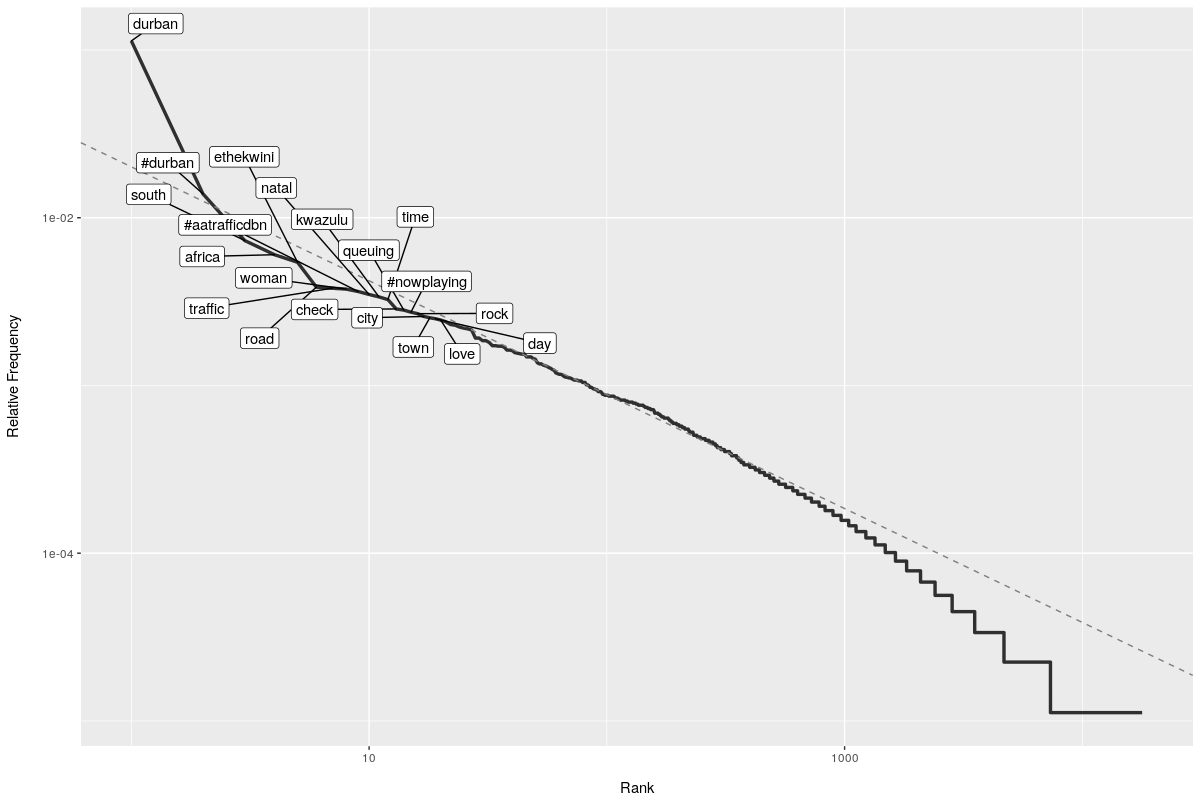

Zipf’s Law is an empirical statistical law which states that for a large text corpus, the frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its rank in a frequency table.

Do the Twitter data conform to Zipf’s Law? The plot below suggests that they do. Certainly for words of intermediate rank there is a clear inverse proportionality between rank and frequency (the dashed line reflects the relationship expected from Zipf’s Law). The deviations at low and high rank are not surprising, and in these extremes the observed frequency of words is commonly less than predicted. The first few lowest ranked terms also deviate from expectations because of the inherent bias in our sample: we have specifically chosen tweets that include the words “Durban” and “eThekwini”, so we should expect their frequency to be elevated.

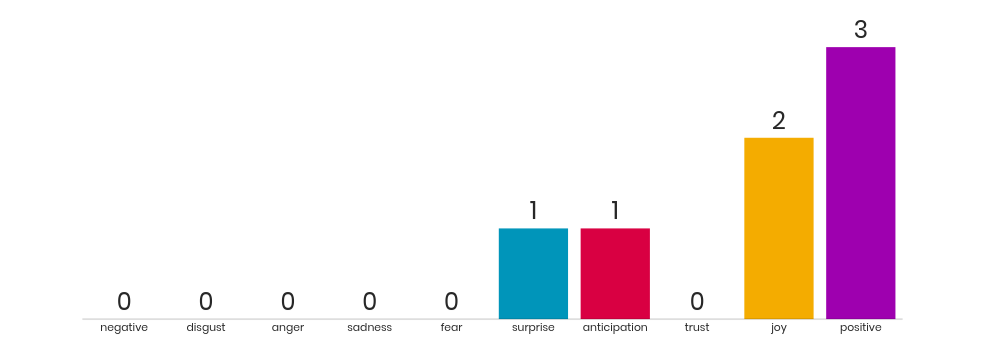

Sentiment

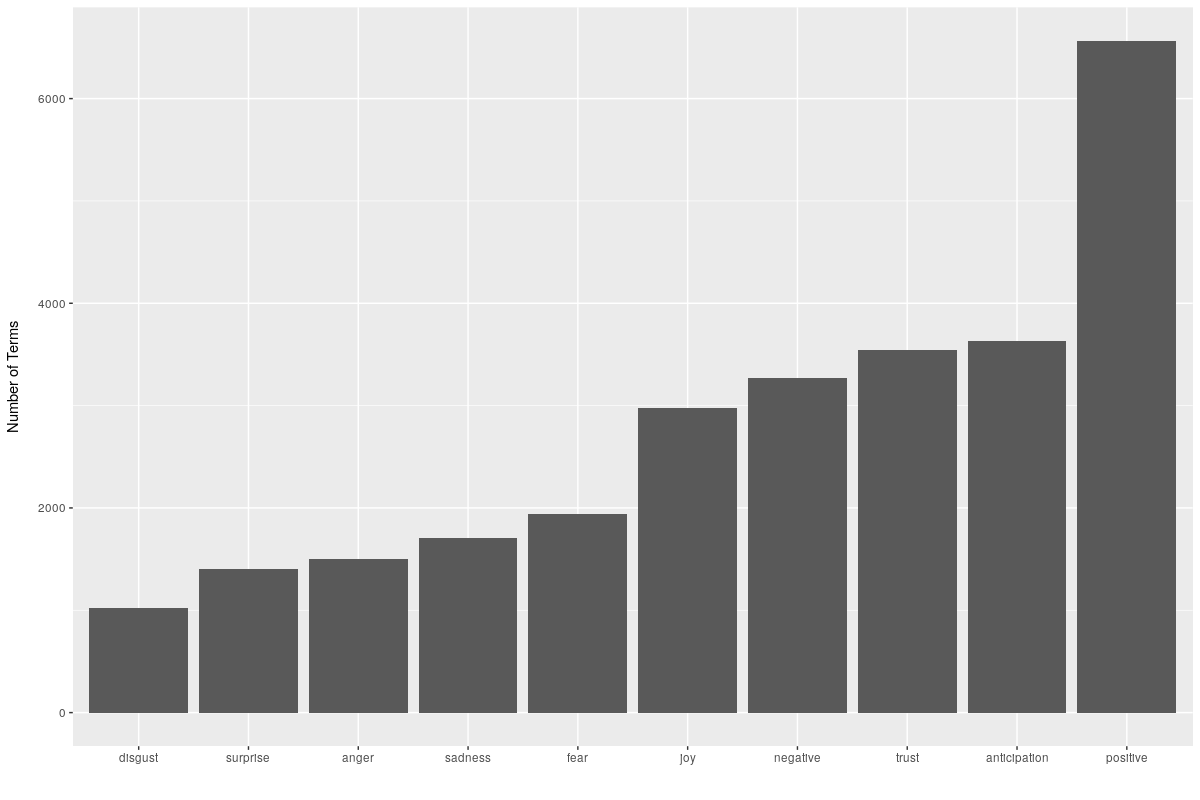

Finally, using the NRC lexicon to get an indication of sentiment yielded the results below. It’s pleasing to see that positive sentiments are in the ascendancy. However there is certainly not an insignificant proportion of negative sentiment.

For the first time I used Mentimeter to get some audience response. Despite the fact that the engagement was low, I was really impressed with this tool and how easy it was to integrate into my presentation.

Word Cloud

Of course, no Twitter analysis would be complete without the obligatory cliché of a word cloud.

Question Time

In the question time following my talk we chatted about whether or not the NRC lexicon is appropriate to an analysis of South African tweets. We agreed that it wasn’t: not only do South Africans normally employ British rather than American spelling (resulting in numerous mismatches against the lexicon), but the South African vernacular and numerous local languages imply that only a relatively small proportion of the terms in the tweet corpus were actually matched by the lexicon.

If one had the time and inclination, then building a sentiment lexicon for South Africa would be a great project!