The paper The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada by Charles Elton and Mary Nicholson is a foundational work in population ecology and wildlife dynamics. They documented the regular, roughly ten-year population cycle of the Canadian Lynx (Lynx canadensis), observed in fur trade records from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

Take a look at the paper. It’s a thing of beauty, from a time when data sets were sufficiently small that you could tabulate them completely in the body of a paper.

Data Repository

Although the paper was published many decades ago, the PDF version is not a scanned image of the printed pages but contains the original, selectable text. As a result, tables and other data can be extracted accurately and completely. I used Textract to gather the data from the tables. Given the clarity and simplicity of the tables I could probably have done this with simpler, local tools. The extracted data can be found here.

Comparison

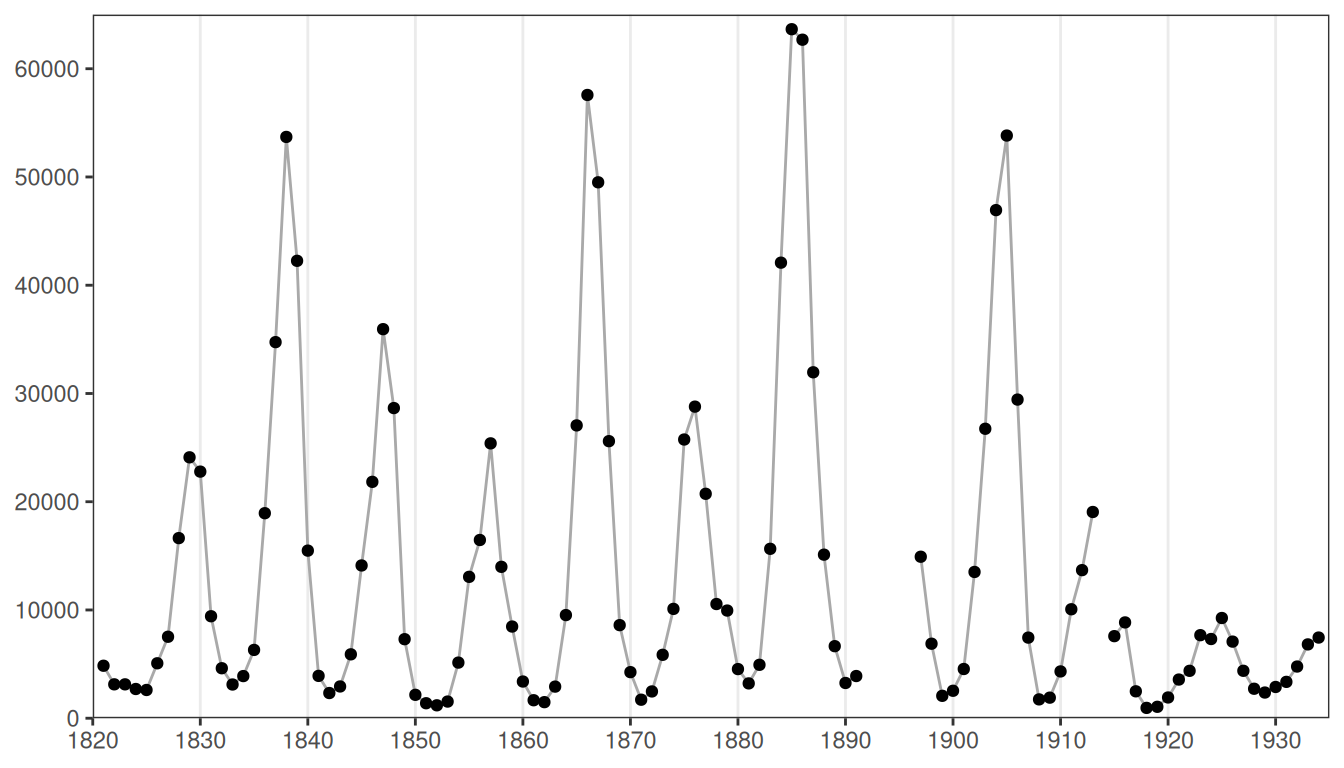

For comparison purposes I loaded the data for Table 4 and created a plot.

Compare with Figure 7, the corresponding plot from the paper.

What causes the regular variation in lynx numbers? Food. The lynx is a fussy eater, with a preference for specific prey: either the snowshoe rabbit or a few varieties of hare. There’s a close predator-prey feedback loop between the number of lynx and the availability of their preferred prey. At the top of the lynx poplulation cycle there’s an abundance of predators. Lots of predators require lots of food. This impacts the population of the rabbits and hares, which start to decline. With less food around times are tough for the lynx and their numbers start to drop. As the lynx population decreases things become easier for the prey, whose numbers start to grow again. More prey causes the lynx population to recover. And the cycle begins again.

Conclusion

Rescuing data from old papers is a bit of an indulgence. But it’s surprisingly fun and worthwhile. For me it’s a useful reminder of how hard scientists had to work to gather data in the past, something which is easily forgotten today when so much of the process can be automated.